Mucus: A Complex Marvel in Health and Ecosystems

Mucus, often dismissed as an inconvenience or a mere bodily secretion, plays a crucial role in maintaining the delicate balance within our bodies. This viscous substance, produced by various mucous membranes, is a complex mixture of water, proteins, cells, and salts. In this comprehensive exploration, we delve into the multifaceted world of mucus, uncovering its surprising functions, importance in our health, and the fascinating ways it adapts to different environments.

The Biochemical Composition of Mucus

The biochemical composition of mucus is a fascinating interplay of various elements, each contributing to its unique properties and functions. At its core, mucus is a viscoelastic gel composed primarily of water, proteins, lipids, salts, and cellular components. Let’s delve into the key components that make up the intricate structure of mucus.

Water: The Foundation of Mucus

Water forms the bulk of mucus, constituting around 95% of its volume. This high water content gives mucus its characteristic viscosity and helps it function as a lubricant and barrier within different physiological systems. The aqueous environment facilitates the movement of molecules and particles within mucus, allowing it to trap and transport substances effectively.

Glycoproteins: Building Blocks of Structure

The structural integrity of mucus is largely attributed to glycoproteins, which are complex molecules consisting of proteins linked to sugar chains. The most well-known glycoprotein in mucus is mucin. Mucins are large, heavily glycosylated proteins that give mucus its gel-like consistency. These proteins contribute to the adhesive properties of mucus, allowing it to adhere to surfaces and trap particles.

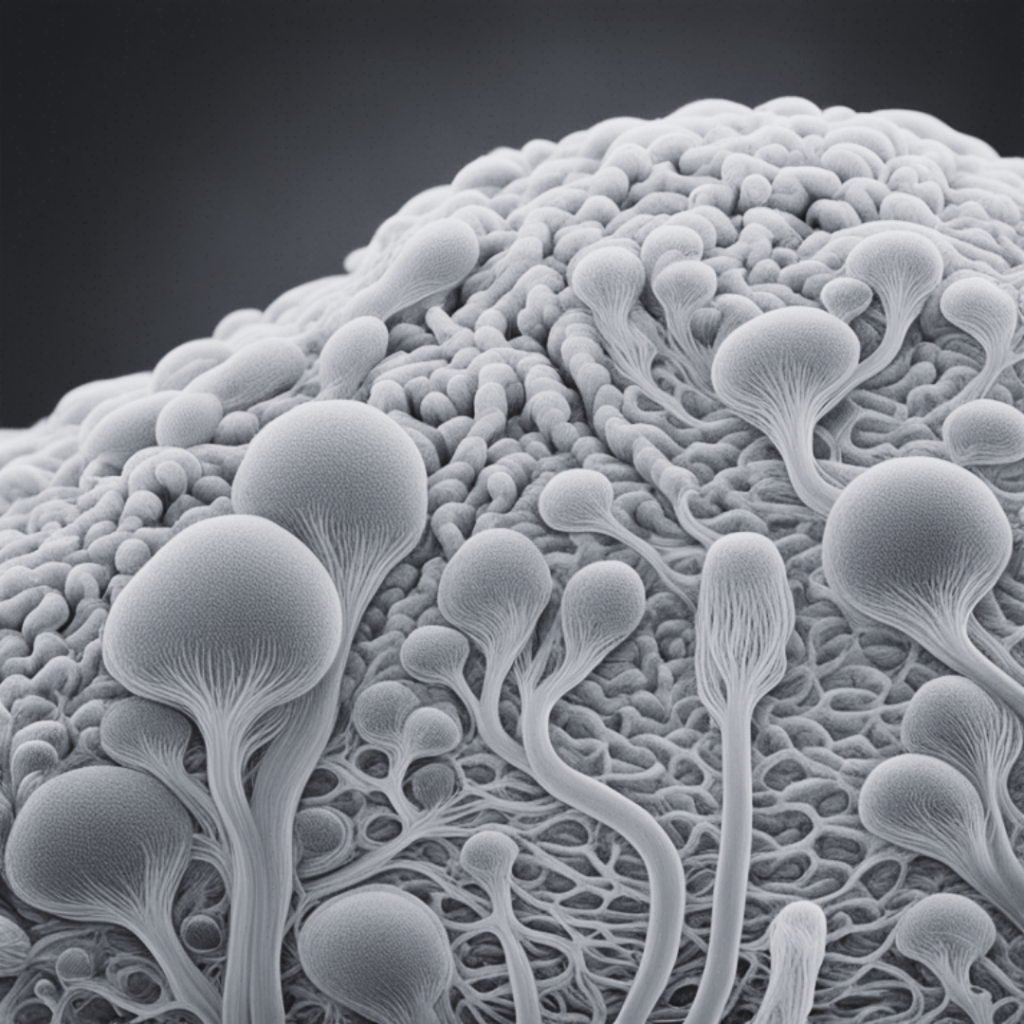

Mucins: The Heroes of Viscosity

Mucins are the principal macromolecules in mucus, and they play a pivotal role in determining its viscosity. These large, thread-like molecules extend throughout the mucus matrix, forming a three-dimensional network that gives mucus its gel-like consistency. Mucins also contain specific domains that interact with water molecules, contributing to the hydration and lubrication of mucus.

Immunoglobulins: Guardians of the Immune System

Immunoglobulins, or antibodies, are essential components of mucus that contribute to its role in immune defense. These proteins are produced by the immune system and are present in various bodily secretions, including mucus. Immunoglobulins recognize and neutralize pathogens, preventing infections from taking hold. In the respiratory and digestive systems, mucus-bound immunoglobulins act as a first line of defense against invading microorganisms.

Salts: Electrolyte Balance

Mucus contains a range of salts, including sodium, potassium, calcium, and chloride ions. These electrolytes help maintain the ionic balance within mucus, influencing its osmolarity and viscosity. The presence of salts is particularly important in mucus covering epithelial surfaces, contributing to the regulation of water content and hydration.

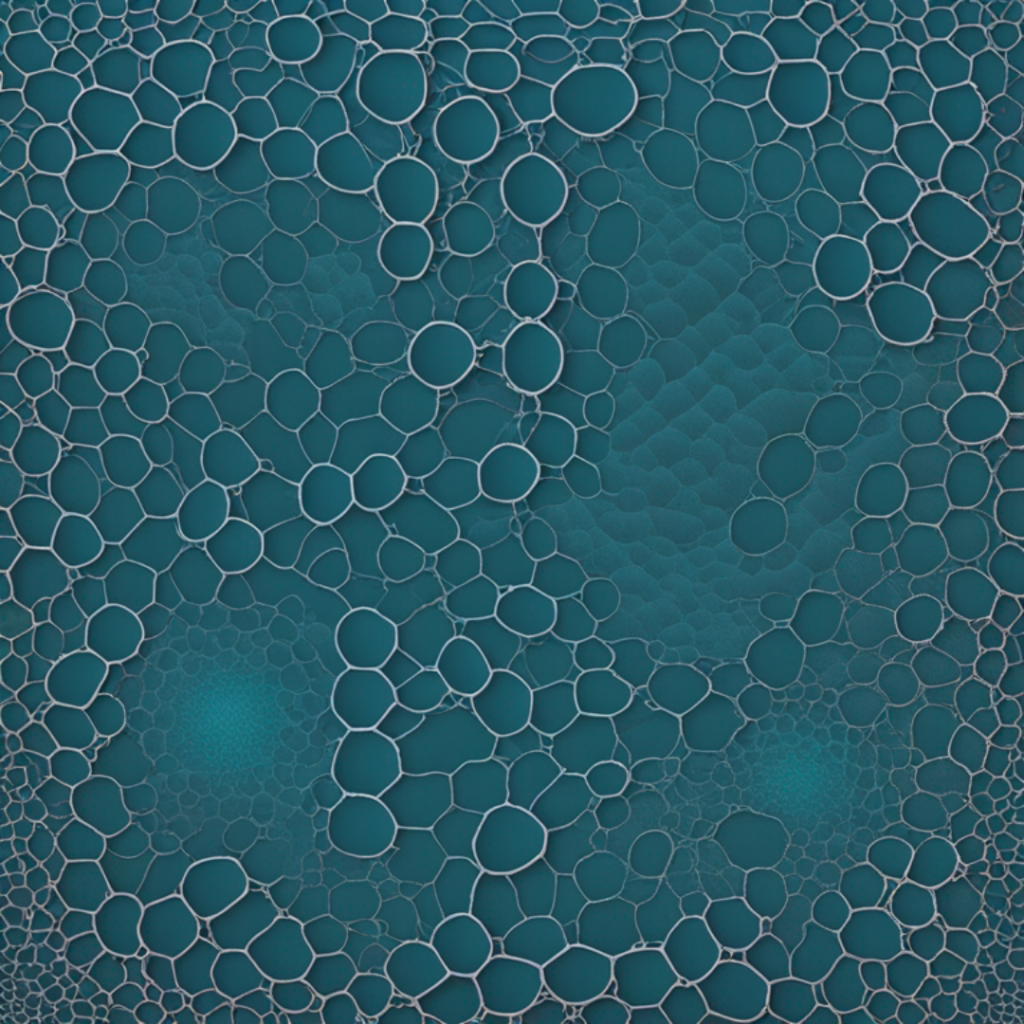

Cellular Components: The Living Dimension

Mucus is not merely a static gel but contains living cells, such as epithelial cells and immune cells. These cells contribute to the dynamic nature of mucus and actively participate in its functions. Epithelial cells produce mucus, while immune cells play a crucial role in detecting and responding to pathogens within the mucus layer.

The Diverse Functions of Mucus

Mucus, often regarded as a simple bodily secretion, reveals itself as a multifunctional marvel with diverse roles across different physiological systems. Its functions extend far beyond being a mere lubricant or barrier, playing crucial roles in maintaining health and homeostasis. Let’s explore the diverse functions of mucus in various parts of the body:

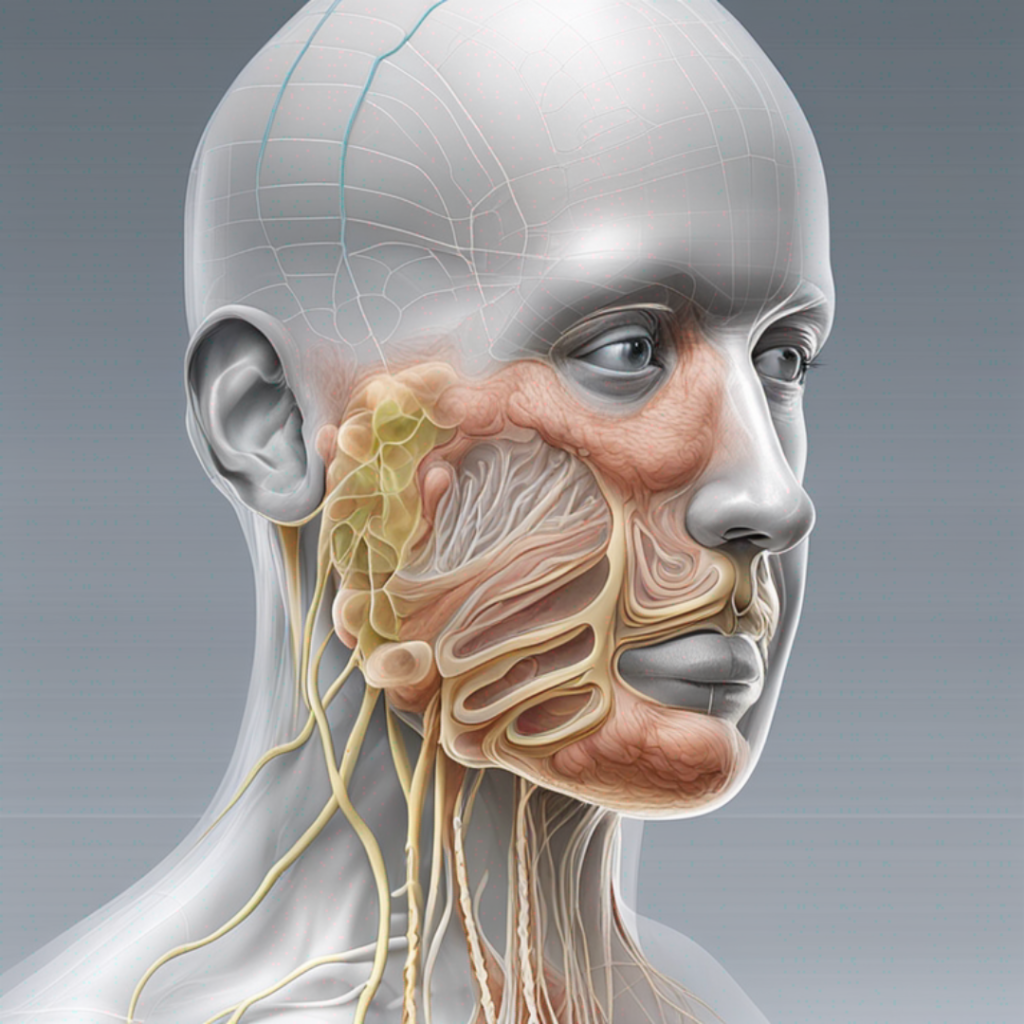

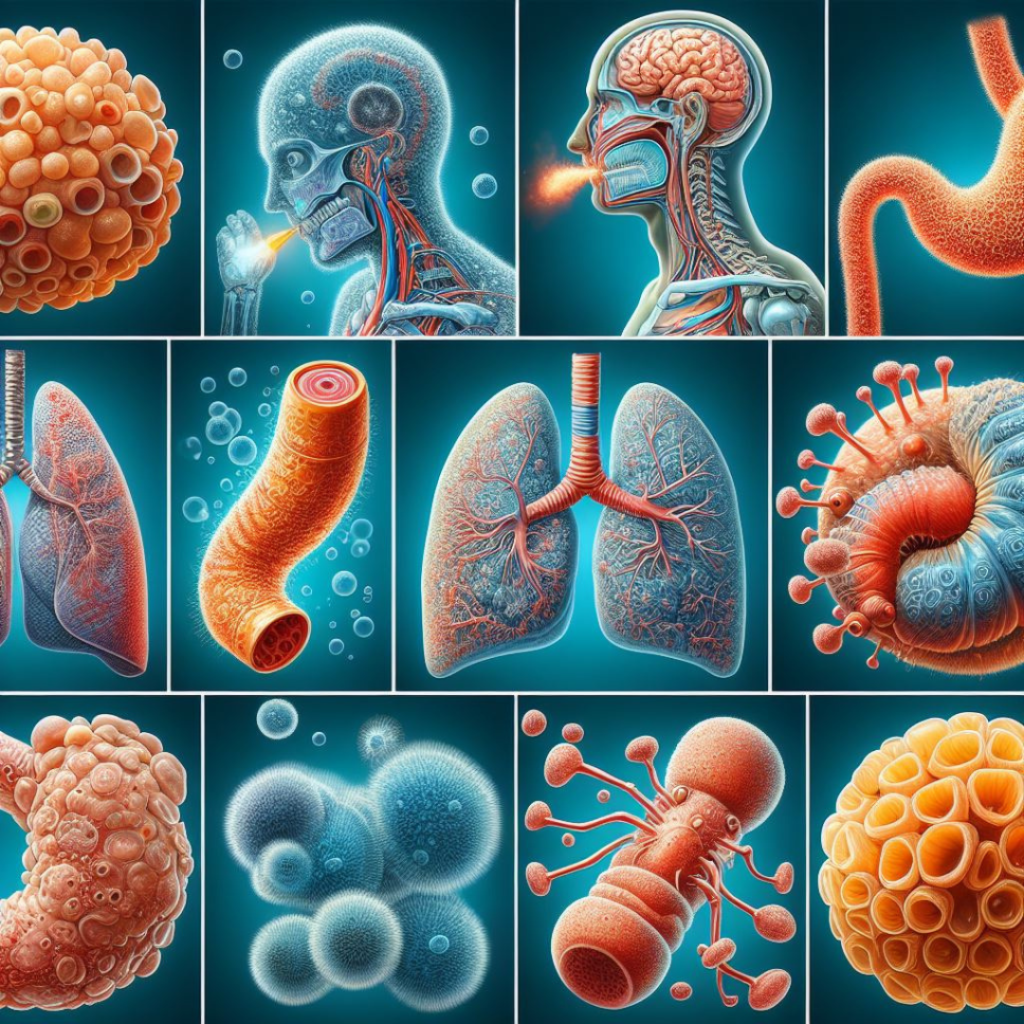

I. Respiratory System: Shielding the Lungs

A. Particle and Pathogen Filtration:

Mucus in the respiratory system acts as a protective barrier, trapping inhaled particles, dust, and pathogens. This prevents these foreign entities from reaching the delicate lung tissues, reducing the risk of infections and inflammation.

B. Ciliary Action and Mucus Clearance:

Collaborating with cilia—microscopic hair-like structures lining the respiratory tract—mucus facilitates the clearance of trapped particles. The coordinated movement of cilia propels the mucus, along with trapped particles, upward towards the throat, where it can be expelled or swallowed.

C. Moistening and Humidification:

Mucus contributes to maintaining the moisture and humidity of the airways, preventing them from drying out. This ensures optimal conditions for respiratory processes and helps protect the lungs from irritation.

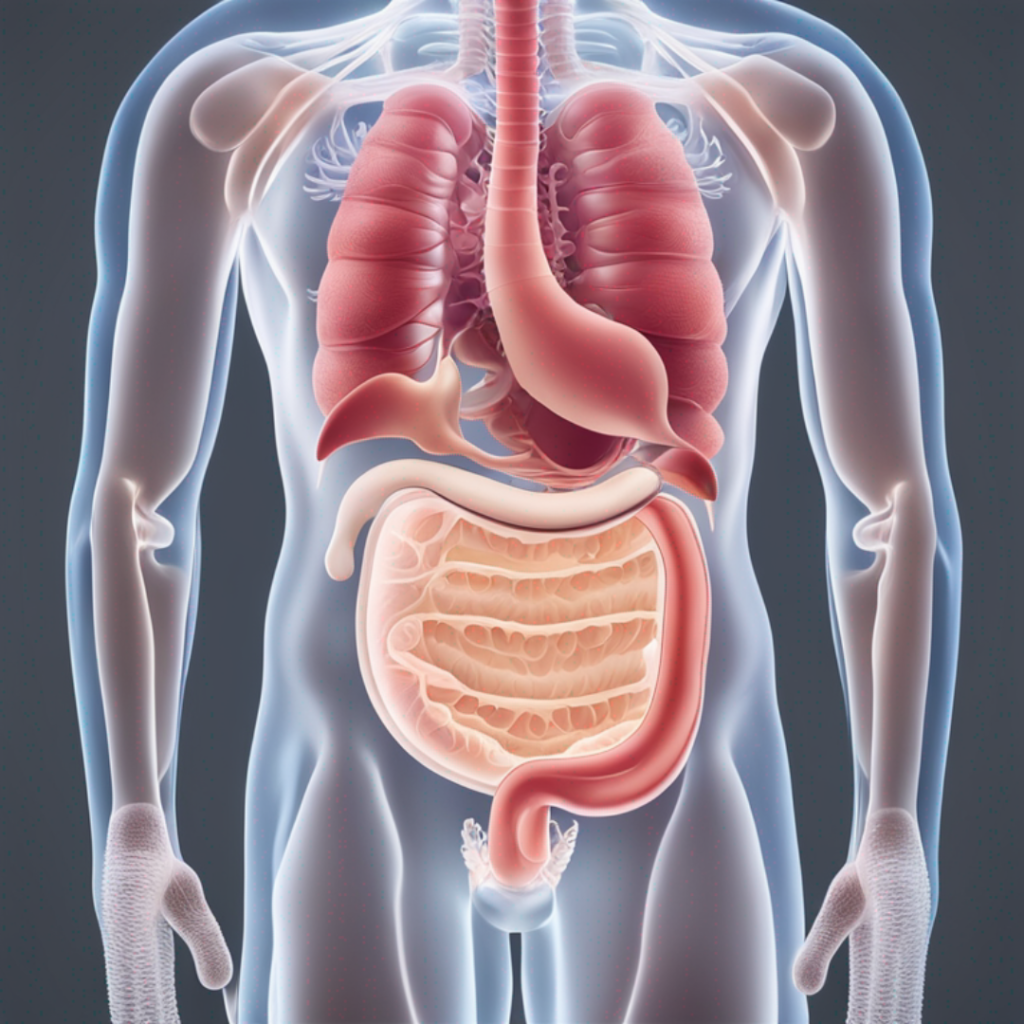

II. Digestive System: Facilitating Nutrient Absorption

A. Lubrication of Gastrointestinal Tract:

In the digestive system, mucus serves as a lubricant, facilitating the smooth passage of food through the gastrointestinal tract. This reduces friction and allows for efficient digestion and absorption of nutrients.

B. Protection of Gastric Lining:

Mucus in the stomach forms a protective layer over the gastric mucosa, shielding it from the corrosive effects of gastric acids. This protective barrier prevents self-digestion and ulcer formation.

C. Enzyme and Nutrient Transport:

Mucus helps transport digestive enzymes and nutrients to the epithelial cells lining the digestive tract. This aids in the absorption of essential substances while maintaining a barrier against harmful microorganisms.

III. Reproductive System: Fostering Fertility

A. Cervical Mucus and Sperm Transport:

In the female reproductive system, cervical mucus undergoes cyclic changes throughout the menstrual cycle. During ovulation, the mucus becomes more conducive to sperm transport, providing an optimal environment for fertilization.

B. Protection of Reproductive Organs:

Mucus in the reproductive organs offers protection against infections, maintaining the health of the reproductive tissues. It also contributes to the formation of the mucus plug during pregnancy, protecting the developing fetus from potential infections.

Mucus in Disease: Friend or Foe?

The role of mucus in disease is a complex interplay that can be both a friend and a foe, depending on the context and the specific conditions involved. While mucus serves as a crucial defense mechanism in various physiological systems, abnormalities in its production, composition, or clearance can contribute to the development and progression of certain diseases. Let’s explore the dual nature of mucus in the context of different health conditions:

I. Chronic Respiratory Conditions:

A. Cystic Fibrosis:

Friend: Mucus in the respiratory system normally acts as a protective barrier, trapping pathogens and particles. In cystic fibrosis, however, a genetic mutation leads to the production of thick and sticky mucus. While this mucus can effectively trap bacteria, it becomes difficult to clear, leading to recurrent respiratory infections and lung damage.

B. Chronic Bronchitis:

Foe: Chronic bronchitis is characterized by inflammation of the airways and increased mucus production. The excess mucus can obstruct air passages, impairing airflow and leading to persistent coughing. In this context, mucus becomes a contributing factor to the symptoms and progression of the disease.

II. Autoimmune Disorders:

A. Sjögren’s Syndrome:

Foe: Sjögren’s syndrome is an autoimmune disorder that affects mucous membranes, including those producing saliva and tears. The immune system mistakenly attacks and damages these glands, leading to reduced mucus production. The resulting dryness in the eyes and mouth can cause discomfort and increase the risk of infections.

III. Gastrointestinal Disorders:

A. Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD):

Foe: In conditions like Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract can disrupt the normal production and function of mucus. This can compromise the protective barrier of the stomach and intestines, leading to tissue damage and exacerbating symptoms.

IV. Mucus and Infections:

A. Respiratory Infections:

Friend and Foe: Mucus is a key component of the immune defense against respiratory infections. It traps pathogens, preventing them from reaching the lungs. However, in conditions like pneumonia, excessive mucus production can contribute to airway obstruction and compromise respiratory function.

B. Urinary Tract Infections:

Friend: In the urinary tract, mucus helps prevent bacterial adherence to the bladder wall and aids in flushing out pathogens through urine. Adequate mucus production is a protective mechanism against urinary tract infections.

V. Mucus in Wound Healing:

A. Chronic Wounds:

Foe: In chronic wounds, such as diabetic ulcers, abnormal mucus production can impede the healing process. Excess mucus can create a barrier that hinders cell migration and tissue regeneration, prolonging the duration of the wound.

Mucus in the Environment

Mucus, a substance often associated with human and animal biology, extends its influence beyond the confines of living organisms to play intriguing roles in environmental ecosystems. In marine and terrestrial environments, mucus serves as a versatile and dynamic tool, contributing to ecological balance, survival strategies, and inter-species interactions. Let’s explore the diverse ways in which mucus functions in the environment:

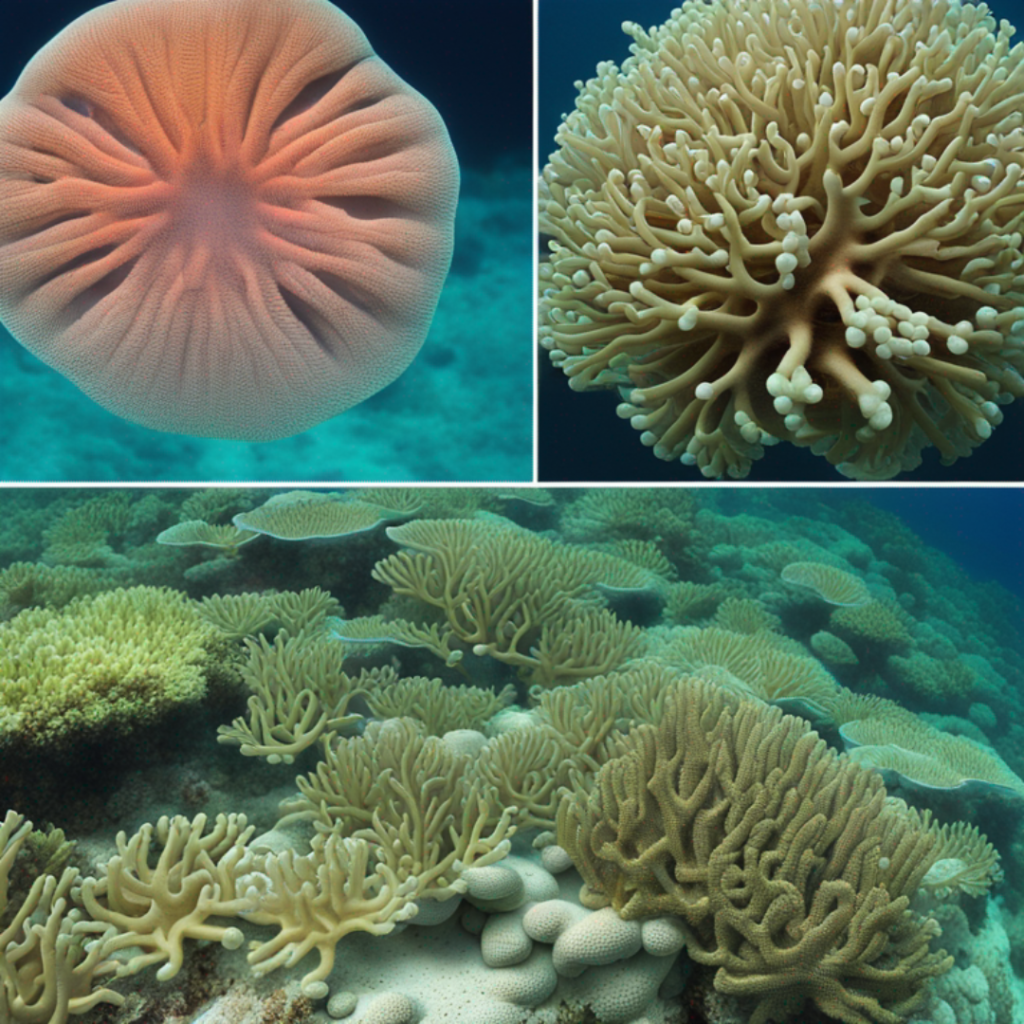

I. Marine Mucus: Oceans of Complexity

A. Defense Against Pathogens:

In marine ecosystems, many organisms, including corals and fish, produce mucus to form a protective layer on their surfaces. This mucus acts as a physical barrier, defending against pathogens, parasites, and harmful microorganisms. It is a first line of defense that helps maintain the health of marine organisms.

B. Communication and Signaling:

Marine mucus plays a crucial role in communication among marine organisms. Some species release specific types of mucus to signal alarm, mark territory, or attract mates. The chemical cues within mucus are essential for coordinating behaviors and interactions in the complex underwater environment.

C. Nutrient Cycling:

Mucus contributes to nutrient cycling in marine ecosystems. Some organisms release mucus as a response to stress or environmental changes. This mucus can serve as a substrate for beneficial microorganisms, promoting nutrient cycling and maintaining the balance of microbial communities.

D. Symbiotic Relationships:

Coral reefs, in particular, rely heavily on mucus production. Coral polyps secrete mucus to trap sediment particles and create a protective layer. This mucus layer fosters symbiotic relationships with microorganisms, such as zooxanthellae, which provide corals with essential nutrients through photosynthesis.

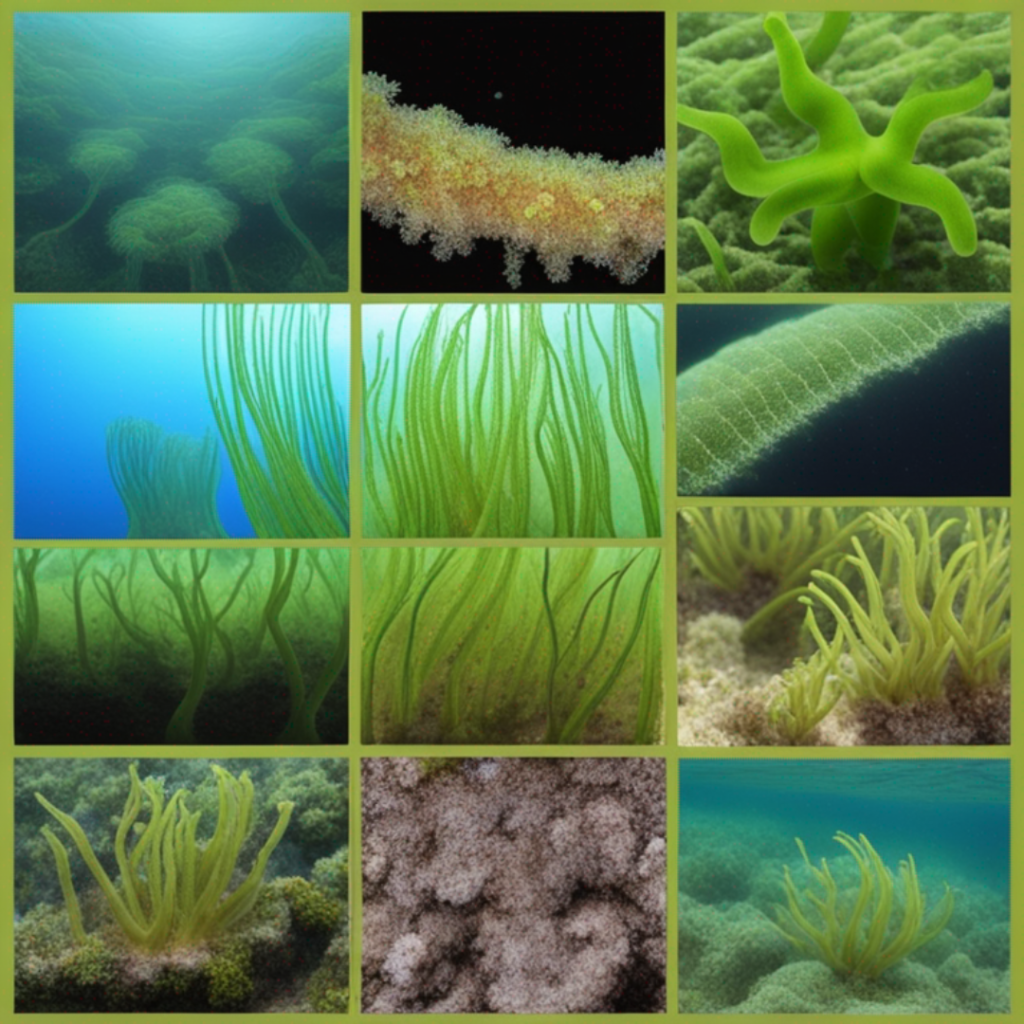

II. Soil Mucus: Unearthing Plant-Microbe Interactions

A. Water Retention and Soil Structure:

In terrestrial ecosystems, plant roots release mucilage—a gelatinous substance—into the surrounding soil. This mucilage helps retain water, improving the water-holding capacity of the soil. It also plays a role in maintaining soil structure, preventing erosion, and promoting aeration.

B. Microbial Interactions:

Soil mucus is a crucial component of the rhizosphere, the region around plant roots where complex interactions between plants and microorganisms occur. Mucilage provides a carbon source for beneficial soil bacteria and fungi, fostering a healthy microbial community that enhances nutrient availability to plants.

C. Seed Germination and Root Development:

Mucilage released by seeds can facilitate germination by retaining water and providing a protective environment. Additionally, root exudates, which contain mucilaginous substances, play a role in root development and the establishment of beneficial relationships with mycorrhizal fungi.

D. Protection Against Pathogens:

Soil mucus contains compounds that can inhibit the growth of certain pathogens. This protective function helps defend plant roots from harmful microbes, contributing to the overall health and resilience of plants in the soil environment.

III. Mucus and Environmental Challenges

A. Adaptation to Environmental Stress:

Some organisms produce more mucus in response to environmental stress, such as changes in temperature, salinity, or pollution. This adaptive response helps organisms cope with challenging conditions and maintain their survival strategies.

B. Biotic and Abiotic Interactions:

Mucus is a mediator of interactions between living organisms and their environment. It can influence the availability of nutrients, the composition of microbial communities, and the response of organisms to environmental changes.

IV. Mucus and Marine Biodiversity

A. Mucus as a Microbial Habitat:

Marine mucus provides a unique microenvironment that supports diverse microbial communities. The complex matrix of mucus serves as a habitat for bacteria, archaea, and other microorganisms. This microbial diversity within mucus contributes to the overall health of marine ecosystems.

B. Food Source for Microorganisms:

Mucus exudates from marine organisms, including phytoplankton and zooplankton, are rich in organic matter. This makes them a valuable food source for heterotrophic bacteria and other microorganisms in the water column. The cycling of organic matter through mucus contributes to nutrient availability in marine environments.

C. Mucus in Coral Reef Resilience:

In coral reefs, mucus produced by coral colonies plays a critical role in the resilience of these ecosystems. Coral mucus contains sugars and proteins that support the growth of symbiotic algae (zooxanthellae) within coral tissues. This symbiotic relationship is essential for the survival and productivity of coral reefs.

V. Agricultural Implications of Soil Mucus

A. Improved Crop Productivity:

Soil mucus, in the form of root exudates and mucilage, enhances nutrient availability for plants. This has significant implications for agriculture, as the presence of beneficial microorganisms in the rhizosphere promotes nutrient uptake, leading to improved crop productivity.

B. Soil Erosion Control:

Mucilage released by plant roots contributes to soil structure and stability. This aids in preventing soil erosion, a critical concern in agriculture. The ability of mucilage to bind soil particles together helps maintain the integrity of agricultural landscapes.

C. Disease Suppression:

Certain compounds in soil mucus have been found to suppress the growth of plant pathogens. Harnessing these natural defense mechanisms could offer sustainable alternatives to chemical pesticides, promoting environmentally friendly agricultural practices.

VI. Mucus and Environmental Conservation

A. Indicator of Ecosystem Health:

Changes in the production and composition of mucus by marine organisms or plants can serve as indicators of environmental health. Monitoring mucus-related parameters can provide insights into the impact of environmental stressors on ecosystems.

B. Restoration Strategies:

Understanding the role of mucus in ecological interactions can inform restoration strategies for damaged ecosystems. Efforts to restore coral reefs or degraded soil environments can benefit from considering the role of mucus in fostering symbiotic relationships and supporting microbial communities.

C. Climate Change Resilience:

The adaptive responses of organisms, including increased mucus production, may contribute to their resilience in the face of climate change. Studying these adaptive mechanisms could aid in developing strategies to enhance the resilience of ecosystems to environmental challenges.

Conclusion: Mucus – A Symphony of Health and Ecology

The often-overlooked mucus, dismissed as a mere bodily secretion, emerges as a fascinating and indispensable player in both the intricate dance of our physiological systems and the delicate balance of environmental ecosystems. Its biochemical composition, ranging from water and proteins to immune components, forms the foundation of its multifaceted functions within the human body. From protecting the respiratory and digestive systems to fostering fertility in the reproductive organs, mucus proves to be a versatile and vital substance.

In disease, mucus showcases its dual nature—acting as a friend in immune defense and a foe when abnormalities disrupt its normal functions. Chronic respiratory conditions, autoimmune disorders, gastrointestinal issues, and infections all highlight the complex relationship between mucus and health.

Beyond the confines of our bodies, mucus extends its influence into environmental realms. In marine ecosystems, it serves as a defense against pathogens, a means of communication, and a contributor to nutrient cycling. In terrestrial environments, soil mucus aids in water retention, microbial interactions, and plant health, offering valuable insights for sustainable agriculture.

Mucus, often a subject of disdain or disregard, deserves a closer look for its pivotal roles in maintaining health, promoting ecological balance, and adapting to diverse environments. As we deepen our understanding of mucus, we unveil its intricate connections to the intricate tapestry of life—within and beyond ourselves.

Disclaimer

The information provided in this blog post is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as medical or environmental advice. Consult with a qualified healthcare professional or environmental expert for personalized guidance and recommendations based on individual circumstances. The author and publisher of this content are not responsible for any consequences arising from the use or interpretation of the information presented.

Subscribe Now for Exclusive Updates and Insights